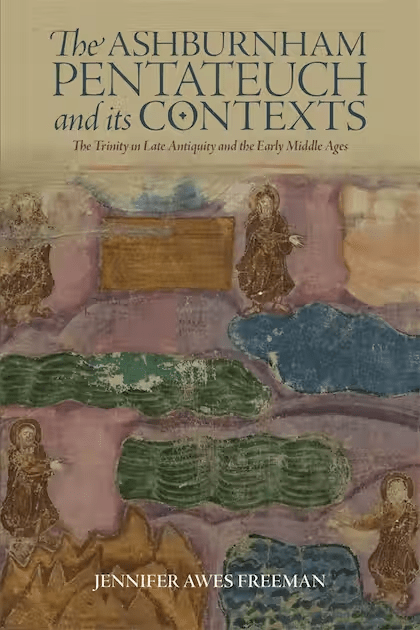

The Ashburnham Pentateuch is an early medieval manuscript of uncertain provenance, which has puzzled and intrigued scholars since the nineteenth century. Its first image, which depicts the Genesis creation narrative, is itself a site of mystery; originally, it presented the Trinity as three men in various vignettes, but in the early ninth century, by which time the manuscript had come to the monastery at Tours, most of the figures were obscured by paint, leaving behind a single creator. In this sense, the manuscript serves as a kind of hinge between the late antique and early medieval periods. Why was the Ashburnham Pentateuch’s anthropomorphic image of the Trinity acceptable in the sixth century, but not in the ninth?

This study examines the theological, political, and iconographic contexts of the production and later modification of the Ashburnham Pentateuch’s creation image. The discussion focuses on materiality, the oft-contested relationship between image and word, and iconoclastic acts as “embodied responses”. Ultimately, this book argues that the Carolingian-era reception and modification of the creation image is consistent with contemporaneous iconography, a concern for maintaining the absolute unity of the Trinity, as well as Carolingian image theory following the Byzantine iconoclastic controversy. Tracing the changes in Trinitarian theology and theories of the image offers us a better understanding of the mutual influences between art, theology, and politics during Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages.

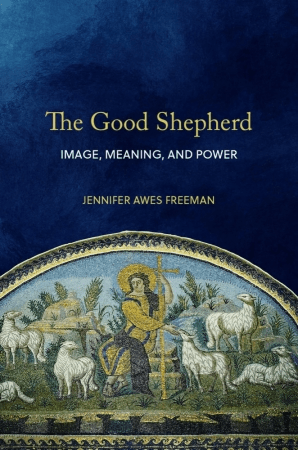

A statuette of Egyptian King Pepi formidably wielding a shepherd’s crook stands in stark contrast to a fresco of an unassuming Orpheus-like youth gently hoisting a sheep around his shoulders. Both images, however, occupy an extensive tradition of shepherding motifs. In the transition from ancient Near Eastern depictions of the keeper of flocks as one holding great power to the more “pastoral” scenes of early Christian art, it might appear that connotations of rulership were divested from the image of the shepherd. The reality, however, presents a much more complex tapestry.

The Good Shepherd: Image, Meaning, and Power traces the visual and textual depictions of the Good Shepherd motif from its early iterations as a potent symbol of kingship, through its reimagining in biblical figures, such as the shepherd-king David, and onward to the shepherds of Greco-Roman literature. Jennifer Awes Freeman reveals that the figure of the Good Shepherd never became humble or docile but always carried connotations of empire, divinity, and defensive violence even within varied sociopolitical contexts. The early Christian invocation of the Good Shepherd was not simply anti-imperial but relied on a complex set of associations that included king, priest, pastor, and sacrificial victim—even as it subverted those meanings in the figure of Jesus, both shepherd and sacrificial lamb. The concept of the Good Shepherd continued to prove useful for early medieval rulers, such as Charlemagne, but its imperial references waned in the later Middle Ages as it became more exclusively applied to church leaders.

Drawing on a range of sources including literature, theological treatises, and political texts, as well as sculpture, mosaics, and manuscript illuminations, The Good Shepherd offers a significant contribution as the first comprehensive study of the long history of the Good Shepherd motif. It also engages the flexible and multivalent abilities of visual and textual symbols to convey multiple meanings in religious and political contexts.

Praise for The Good Shepherd:

“Jennifer Awes Freeman has provided readers with the first comprehensive examination of one of the most well-known motifs in early Christian art: the Good Shepherd. Awes Freeman examines the earliest antecedents of the shepherd motif and allows her audience to realize how early Christians synthesized and reimagined existing conceptions of the Good Shepherd, weaving them into the uniquely Christian trope it is today. Moreover, Awes Freeman’s triumphant work exhibits how much can be gleaned by studying Christian history through the lenses of art, imagery, and material culture. Her work on the Good Shepherd proves how valuable her methodology is, and she provides a lasting testament to this pivotal motif in early Christianity and beyond.”

~Lee Jefferson, Nelson D. and Mary McDowell Rodes Associate Professor of Religion, Centre College

“Jennifer Awes Freeman’s study takes a fresh look at an iconography that has been so long defined in art history that it is hardly questioned, proving that Early Christian subjects with established meanings can indeed be fruitfully re-examined. She traces the motif of the ruler as shepherd through literary and visual precedents over millennia of Near Eastern, Greek, and Roman cultures to substantiate quite convincingly the argument that Christ as the Good Shepherd in Early Christian art was no humble image used to represent Jesus, but an exalted one. The author further demonstrates how the idea of the ruler-shepherd was understood in the Christian Roman Empire and the Early Middle Ages to underscore the role of Christ as shepherd of his flock, sacrifice, and law-giver, as well as to augment the idea of the Christian ruler as a Christ-like shepherd of his people who also followed the example of King David and other Old Testament ruler-shepherds.”

~Katherine Marsengill, Independent Scholar, Brooklyn, New York

“With striking originality and sympathetic insight, The Good Shepherd traces a compelling history of this haunting figure from ancient Mesopotamia through the Middle Ages. The lives of shepherds—harsh, isolated, and dangerous—provided ancient monarchs with a potent image for the challenges of kingship. From the Hebrew shepherd king David and the poetic shepherds of ancient Greece and Rome, early Christians drew further inspiration for their vision of Jesus Christ as a Good Shepherd: king, priest, pastor, and sacrificial victim, a figure who gains new life in the swiftly developing urban culture of twelfth-century Italy. Beautifully illustrated, The Good Shepherd weaves a poignant story of beauty, mystery, and compassion through the ages.”

~Ingrid Rowland, Professor in the Department of History and the School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame